Digital Archiving Oral History Cassette Tapes

Published on .

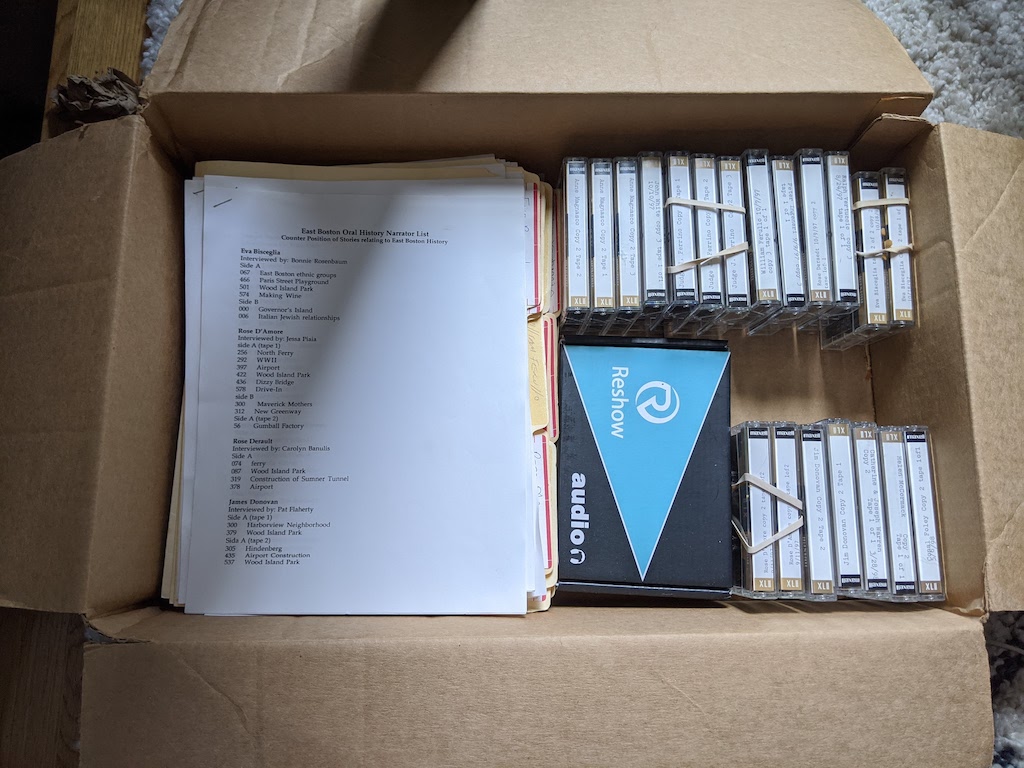

For no particularly good reason, I like archiving things. I haven’t seen many things disappear in my life, but still I like pushing physical things across the digital divide, where they are simple to enjoy and share. So when I heard that the East Boston Greenway Council’s oral history interviews from 1997 were sitting on cassette tapes, I agreed to digitize them. I have time—it is a pandemic after all—but still when the box of 21 tapes arrived, I was daunted. This is the story of archiving them.

The first step as purchasing a cassette tape digitizer. Luckily the top result on Amazon had decent reviews, so within a few days a “Reshow Re-006 Super USB Cassette Capture” arrived. I expected to fuss around with drivers, but miraculously it worked as soon as I plugged in it’s USB cable and configured the Audacity software to use it as input.

I put in the first tape and within a few clicks I was recording, except I hadn’t yet figured out timed recording so I babysat it for 90-minutes. Turns out Audacity has a “Timer Record” function for exactly this purpose. Once it was captured, I discovered that the noise was significant. Luckily, Audacity once again had a “noise reduction” effect. It took me some time to figure it out, but as the instructions says, you select a few seconds of noise, click “get noise profile” then select the entire track and do “Noise Reduction…” On my 2016 MacBook, it takes about 1 second to process 1 minute of audio. The results were mixed, until I discovered that it is very important to select a good sample, and often the best sample was in between sides A and B (not at the beginning, since a “good” sample is one that has the feedback from the moving tape, but no voices. I also didn’t understand at first that “Save” meant keeping a lossless copy of the audio (which requires a couple gigabytes of disk space for a 90 minute tape.) I decided to apply the “Loudness Normalization” filter too, although I’m not sure it changed much. Then I exported to a variable rate MP3.

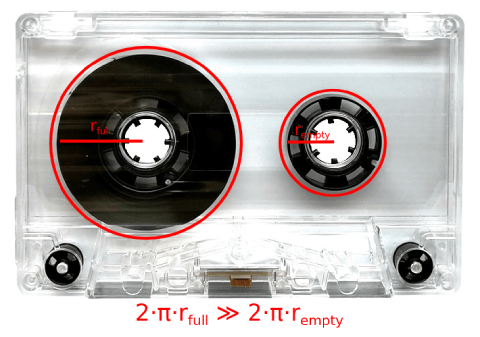

The next challenge was labels, which are named points in time. Around 1998, the project team carefully noted counter positions for noteworthy topics. Even once I discovered that a “counter” meant a revolution of the spool, I still wasn’t sure how to convert them to timestamps. The problem is illustrated below, where the figure highlights the fact that early in the tape a single revolution might contain several seconds of audio, whereas an almost empty spool contains barely 1 second. So, its non-linear and you need some polynomial formula solution.

The final formula isn’t that tough, but it took me longer than I’m willing to admit to get there.